Our dedication to Racial Equality and Social Justice (RESJ) spans decades. Learn more about our RESJ Initiative

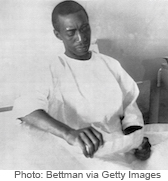

Clyde Kennard

When it comes to Black civil rights progress, Clyde Kennard’s story is a painful reminder of how much individual struggle and suffering can be endured in the fight to access and achieve basic human dignities.

When it comes to Black civil rights progress, Clyde Kennard’s story is a painful reminder of how much individual struggle and suffering can be endured in the fight to access and achieve basic human dignities.

Kennard was born in 1927 in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. When he turned 18, he joined the military, and served for seven years, first in Germany post-WWII then in the Korean War, before his honorable discharge in the early 1950s. He enrolled at the University of Chicago and was three years into a bachelor’s in political science before his stepdad died, when he decided to move back to Mississippi to help his mom raise the farm he bought her with his military savings.

While in Mississippi, he aspired to complete his degree at the nearby Mississippi Southern College, which was an all-white college. He applied three times: the first time (in 1955), he lacked a required five letters of recommendation from previous graduates; the second time (in 1958), he withdrew his application after being successfully convinced by a congregation of the school’s president, black conservatives, and the governor of Mississippi that ‘the time was not right for integration’; the third time (in 1959), he was rejected on a technicality, and on his way back from his meeting with the college’s president, he was pulled over by cops and falsely charged with speeding and possessing alcohol in a dry town. (He didn’t drink.)

After this, Kennard was ready to make a federal case of the matter, and went on to advocate publicly for his own inclusion and admission into his home state’s exclusively white educational system. The anti-integration establishment aimed to silence him, to avoid federal consequences, and ultimately succeeded by framing him for the crime of masterminding a $25 ‘heist’ of chicken feed. His punishment, which came down from an all-white jury, was seven years of hard field labor. While serving his sentence, he became terminally ill with cancer, was refused treatment, but was still expected to perform labor. Just a few short months after his sentence was commuted by the governor, who was facing immense political pressure, Kennard died.

In 1959, Kennard said, "[W]e have no desire for revenge in our hearts. What we want is to be respected as men and women, given an opportunity to compete with you in the great and interesting race of life. We want your friends to be our friends; we want your enemies to be our enemies; we want your hopes and ambitions to be our hopes and ambitions, and your joys and sorrows to be our joys and sorrows."

Read Clyde Kennard’s story in greater detail